Spatial Grammar

Our life experiences are our constellations; from small details such as enjoying a snack to the really big questions. We are forever blending objectivity and subjectivity. In Tapissary, we measure the degree of that interchange with distance and special attention to the words that describe it.

Orientation

(Quick note: The spatial grammar shown on this page is based on the basic grammar on another tab of this site. The page here might make more sense to you if you first check out the basic grammar page).

In any given moment, we as human beings are subconsciously judging the world around us in terms of how real things seem, or how imaginary they seem, and all the degrees in between those two polarities. In Tapissary, we lift that dichotomy to the surface. If you pay close attention to almost any conversation, you might discover that most of the communication is subjective, meaning that we tend to speak with one another via opinions, beliefs, imagination, and emotions. Of course, if you find yourself in a meeting of scientists, doctors, or mathematicians, the conversation may give more light to the objective.

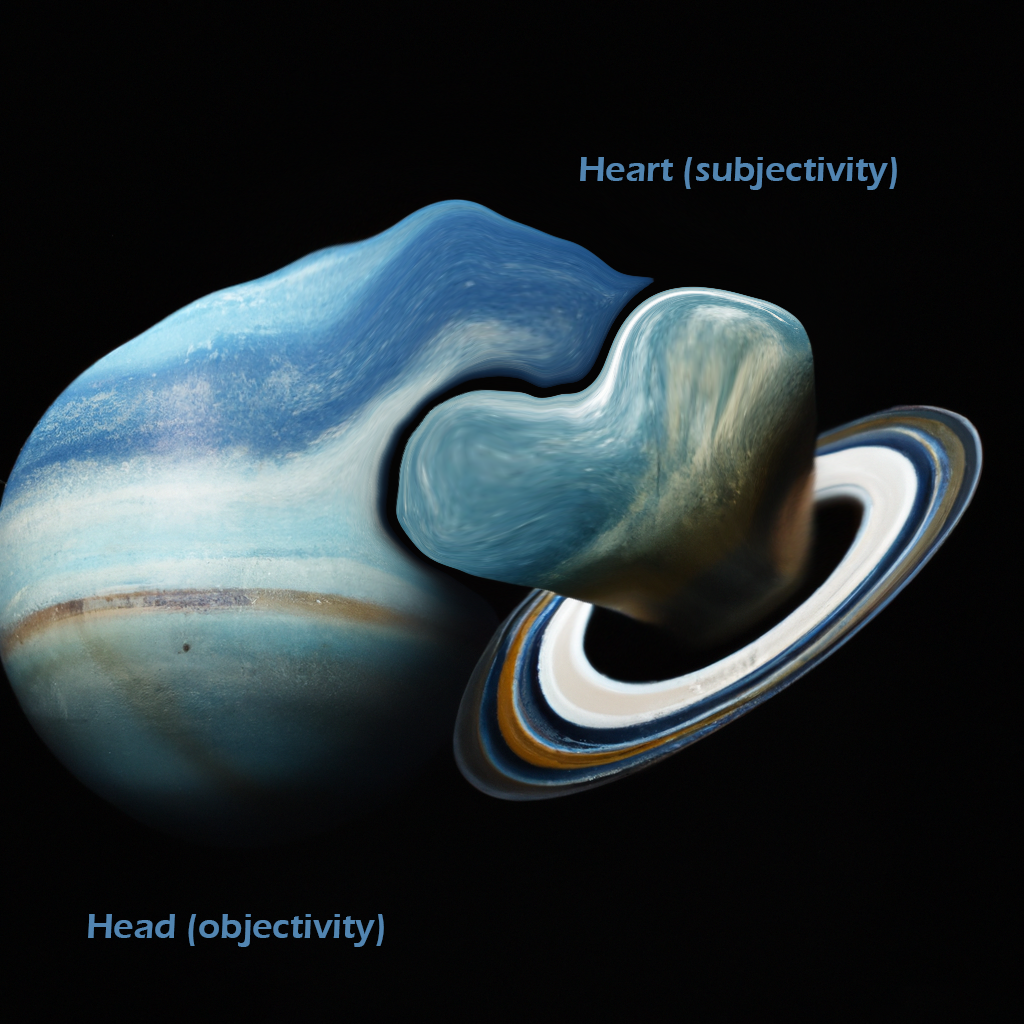

In spatial grammar, the two orientations (objectivity and subjectivity) relate to each other by way of the abstract distance at any given point between them. That sounds like a mouthful, but I’ll show how this might look in the mind’s eye:

As you travel from one orientation (or we could also call it a state for brevity) to the other, say from hard facts (objectivity) toward emotion (subjectivity), qualities along that path increasingly favor the influences from the opposite side the closer you get to it. By the time you reach the core of the emotional state, everything there is purely subjective, purely opinion, or any other traits of subjectivity. The journey between the two passes through captivating territory: our lives.

In 1987, I invented the cyclic grammar for Tapissary. Though it has become archaic since mid-2022, its influence on spatial grammar is strong. You might say that when I created spatial grammar that same year, it is rather a cousin of the cyclic system rather than a whole new concept. And it is far simpler to use than the cycles.

A note to bear in mind: While I am posting the information now about spatial grammar, it is a wholly different perspective than how I usually think. I did not use any reference from existing languages for this kind of grammar, which means I have to figure out how the unique system works from scratch. It has to make sense and it has to be economical - meaning it should use as few parts as possible to convey a large picture. The saving grace is that spatial grammar has close links to my previous cyclic grammar which gives me those years of experience. The challenge may take yet some time to truly assimilate the world as the distance between imagination and logic, so I apologize in advance if at any given time in the future, I find the need to alter something.

In the picture above: The cord that measures the distance between the cores of Heart and Head. The heart state blooms with color and activity to represent the imaginative, while the head state is clear and organized.

We arrive at port.

All aboard, ship now departing for the Heart State! The journey is everything you could ever dream of, and everything you would ever wish to avoid. Both perilous and great adventures ahead. It’s your trip, and on this ship, you are captain of your experiences. Following are the tools for your journey.

The Shades of Logic and Imagination

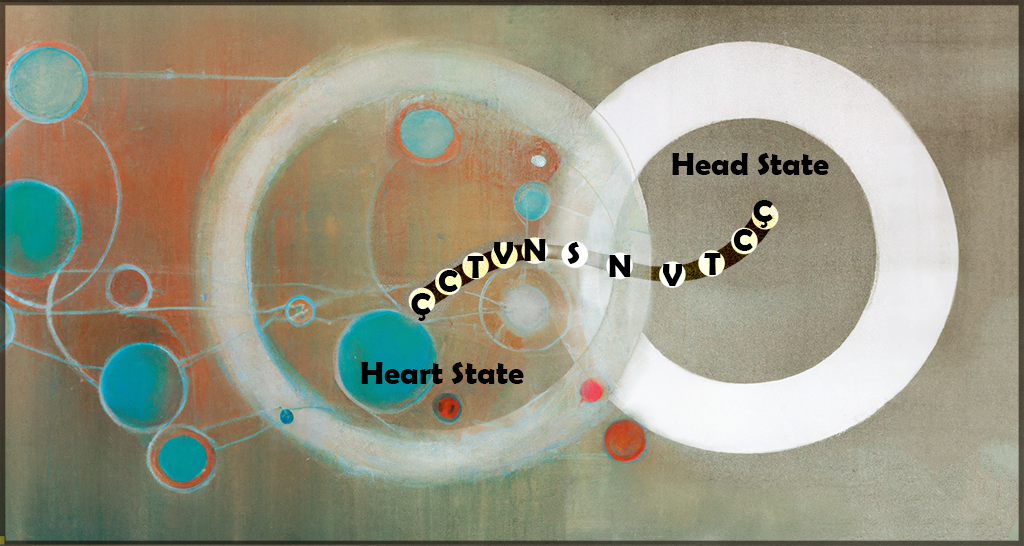

There is an organic cord that connects the Head to the Heart. At the core of the Head, is pure logic, and in Tapissary, purity of a region is rendered with the sound Ç. Likewise, at the core of the Heart we find pure emotion, and for its purity it is also Ç, because Ç indicates the very core. The core of Heart and Head are opposites, yet they both use Ç as their core. It’s important to note this because Ç by itself is meaningless without the context of its position. In the Head state, Ç means logic, in the Heart state, Ç means imagining. Once we leave the core of either Heart or Head, we begin to find mixtures between the two; the mixtures are no longer pure. Think of it this way, suppose Heart were red and Head were blue. Between the two, you mix gradually from red to blue. Head is pure blue, Heart is pure red, but the cord between them is a gradation of purple. In the exact middle between them, it is an exact purple, while the shades closer to Head would be blue purples, and the shades closer to Heart would be red purples. Instead of color, we are describing the shades of logic and imagination.

What it’s like inside the coordinate

Last night I had a nightmare. In the room there were many people. The atmosphere was quiet and sad. Some of the people left. As time passed, fewer remained, until there were only three women in a group sitting on a sofa and chairs, posed as if they were in a painting. I was the only other person in the room, but they did not seem to notice I was there. One of them may have been sick. And then, in the gray approach of evening, the women and light vanished. I was alone in an abandoned town. I needed to find a bathroom in one of the bungalows in the area. It was dead quiet. There were no lights anywhere. No signs of life. The bathroom was dark and dingy, and I decided to turn around and find another when at the door I saw a man twice my size, still as a statue in the gloom. I could not see his face; everything was a blur in the sour dimness. My heart beats and irregular breaths betrayed my vulnerability. He didn’t look at me, but I knew he waited for me. I couldn’t yell, I couldn’t run. Walking was a great effort, I only managed two or three steps. In this dream, I was at the core of the Heart state.

Mechanics

Looking at the picture of the states above, you may notice that there are two intersecting circles, which represent the two states: Heart and Head. The letters on the chord that connects the center (or core) of each state are symmetrically plotted. Do you see that each core begins with Ç, the next neighbor is then C, then T, then V, followed by N, and finally S is right in the middle between them. S is the furthest distance you can be from the core of a state. It signifies that you come from one state but are now crossing into the border of the next. Each letter has specific qualities it represents. When you decide where your communication is in the spectrum of logic and imagination, the letter you choose will go into the subject. We’ll see how to do that shortly. In addition, the verb in your phrase will need to accord with the properties of either Heart or Head. It’s at this point where you have the option to be real creative with your vocabulary.

Frequency

Even though spatial grammar needs only pop up once or twice per paragraph to set the tone, it is always understood to be present, whether you use it or not. By default, it is assumed that the most common state is that of the T distance in the Head state. It is factual but not exact. An example would be to say it’s 90 degrees Fahrenheit in the room, maybe it’s really 87 degrees. In general, that is close enough. T distance in the Head state can be quite flat if you never stray from it, but it’s the mundane that makes it the default since you are staying neutral. The mundane can backfire of course. If you are describing something that you feel emotional about, but use the default, your phrase “I passed a large traffic accident on the way here” would sound like the accident nevertheless wasn’t of any consequence. Whereas in spatial grammar, you might say: My passage-(N) intrudes a large traffic accident on the way here”. This falls squarely within the Heart state emotionally, however because it is also a fact, it is in N position which skirts objectivity. Don’t worry about that now though. I’ll explain the process step by step. All the above is an overview before getting into the details.

Application: now we can begin to build a phrase.

Keeping the information above in mind, about why and what spatial grammar is, let’s start to use it. The three following steps will show you how to construct a spatial phrase.

Step 1: Deciding where you are along the cord.

Distance Markers

Ç

At the very center of either the Heart state or Head state, we find the first coordinate which is represented by the sound Ç. Because the Ç stands within the core itself, it takes on the full essence of the state.

Ç in the Heart state refers to pure fantasy, emotion, or belief. It is what is probably least logical.

Ç in the Head state refers to the scientific approach or logical common sense. It is what is probably most logical. Absolute truth.

C

In close proximity to the core, we arrive at the C marker. If the Ç stands inside the core, imagine C as a close by visitor who stays next to the core at the distance we stand when in conversation with another person. Since C is not in the core, its travel has begun away from the center and toward the distant other state. A little mix occurs here, emotion and belief begin to mix with just a hint of logic.

C in the Heart state refers to what is less probable in relation with logic.

C in the Head state refers to what is presently occurring, and truthful.

T

T is at the midpoint distance. Imagine T to be within your range, but spatially speaking, standing at the other side of the room.

T in the Heart state refers to what might be possible.

T in the Head state refers to what is common knowledge, but which has logical backing.

V

V is far away from the speaker. Abstractly speaking, imagine it a street or two away.

V in the Heart state refers to what is probable, even though we are still in the context of feelings.

V in the Head state refers to what is not imminent or did not actually occur.

N

N is very far away from the speaker. It could be the next city, or even the next galaxy. Please understand that when I talk about the physical distances of a city, galaxy, person across the room, etc., these are just concepts to help explain how distance is divided in Tapissary. It has nothing to do with galaxies or being across the room. The examples are meant to help visualize distances. And here’s a historic note: the reason distances are separated this way is because the articles of distance do specify the spacing as outlined above. The articles of distance originally were placed inside the host word. Now, the article is dropped, but the distance marker remains. Regardless, the old system using the articles, and the new, simplified system using only the distance marker fulfill the same function.

N in the Heart state refers to something being absolutely probable, yet still in the context of some doubt because we are still in the Heart state.

N in the Head state refers to something not occurring.

S

S is the transitional distance marker. This is when you step from one state into the other. You are crossing border control.

S in the Heart state tells of one’s belief being held onto, while knowing it is false.

S in the Head state refers to abandoning what you know is factual. An example: You are in a situation where you know you will be punished if you reveal facts that go against the beliefs of your listeners, so instead, you support their side of the issue.

Step 2: Rephrasing.

Building the new subject.

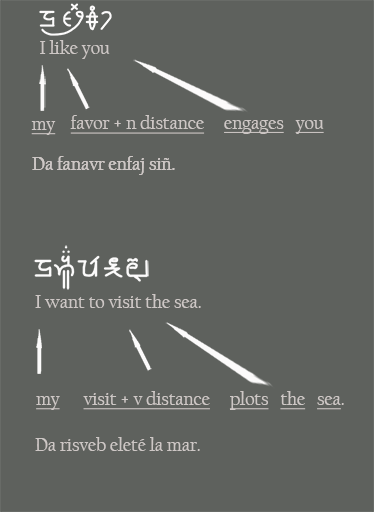

Let’s take the example of a simple phrase “I like you”. The verb is ‘like’, and we will turn it into a noun equivalent, something simple like ‘liking’, or any other noun you feel communicates your context such as ‘appreciation’, ‘enjoyment’, ‘adoration’.

The original subject becomes possessive. “I” becomes “my”. “I like” is now “My appreciation”, or “My liking”, or “my favor”, etc. So, what had been the main verb is now the new subject.

An additional note about possessive pronouns:

The possessive pronouns we saw in the basic grammar (jda, jdé, jdi, cré, cañjo, jdë and jdir) are also used in spatial grammar, however when they precede the subject, the ‘j’ is usually dropped. Instead of saying “My favor” as “Jda favr”, it’s usual to drop the ‘j’ which would give: “Da favr”. The shorter forms of the pronouns are da, dé, di, cré, cañ, dë, and dir. (The çelloglyphs are the same for the J forms and the shorter forms). In any other part of the sentence however, it’s better form to keep the ‘j’ intact.

The verb.

Verbs of the heart, and verbs of the head.

The verb that follows the new subject is where you will distinguish which state you are in. The class of verbs that fall under the Heart state refer to subjective qualities, such as emotion and opinion (to engage, to insist, etc.) The class of verbs that fall under the Head state refer to objective qualities, such as logic and verbs of stillness or being (to stand, to contain, to exist, etc.) The lists are as wide open as you wish, but caution is called for here, since you must communicate clearly to the listener which state you intend by the verb you have chosen. If the listener is unsure, they may interpret your phrase quite differently from your aim. “I like you” as “My appreciation ENGAGES you” is obviously in the Heart state, while “My appreciation STANDS on you” is the Head state. But if you use a verb in the gray area, you may end up communicating the opposite state unintentionally, and instead of professing your appreciation of someone, you may be saying “I have no appreciation of you”. The verbs in the following list are considered fixed, so they can be used without worry.

A small assortment of fixed verbs for the Head and Heart. Notice that ‘understand’ is a heart verb, whereas ‘know’ is a head verb. The reason for this is that knowledge may or may not be factual, but it is available to both humans and computers. Whereas understanding requires seeing the larger picture, putting the knowledge you have into context, and weighing its validity. You can use the following fixed verbs or come up with your own unfixed verbs. The possibilities are numerous.

Heart verbs

Dream …………… Onnixo

Understand …… Lamath

Cheat ……………. Jëc

Plot ………………. Eleté

Engage …………… Enfaj

Inspire …………… Izpir

Nurture ………… Lazet

Encourage ……. Dataxj

Await …………. Mwa

Influence …….. Aw

Promote ………. Jazot

Dominate …….. Csiñsiñ

Trespass ……… Ramam

Recommend …… Lamend

Anticipate ………. Denci

Accuse ………… Agcuz

Insist ……………. Fistxan

Imagine ………. Majin

Head verbs

Stand ……………… Stecom

Sit ………………….. Bes

Occupy ………….. Maiwan

Comprise ………. Coñpres

Limit ……………… Thiñmiñt

Populate ……….. Populé

Exist ………………. Cë

Last ……………….. Dur

Inhabit ………….. Ahabat

Hold ………………. Hoffel

Wait ……………… Atañd, or Çec

Remain …………. Narest

Contain ………… Padtén

Check ……………. Jec

Count …………….. Numérot

Know …………….. Lahha

Step 3: Inserting the distance marker.

Now I refer to the Distance Marker chart a little above. This is the third and last component you need to complete a spatial phrase. Distance markers are infixes, applied the same way as verb tense markers. In fact, they physically replace verb tenses which are not used at all in spatial grammar. Time is handled through context which we will look at a little later. Please don’t worry about that yet, just resign yourself to think consistently in the present tense while expressing spatiality. Now is the time to mention that verbs of volition (want, desire, need, etc.), modal verbs (must, should, etc.), verbs of ability (can, could), also do not have a presence in spatial grammar. You cannot say “I want to go to the airport with you”, or “You should try the new cereal”, or “We can make a difference”. All these sentences replace those initial verbs with distance. That’s where thinking in a different mode comes to play. If I ‘want’ a sandwich, one of the spatial ways to express that is ‘My possession(V distance) imagines a sandwich’. The verb ‘imagine’ signifies that you are in the Heart state, and the V distance shows how far you’ve traveled toward the Head state to a coordinate that includes an equivalent concept of ‘want’. It is not an exact translation of the word ‘want’. Notice that the V distance also includes probability, ability, and the concept of should. In spatial grammar, you are dealing with the distance toward, or away from a given state. It is helpful not to think in terms of vocabulary, but rather the concept of what does it mean to have gone a specific distance from objectivity toward subjectivity or vice versa. Even the negative and affirmative rely on distance. (Notice on the chart how negation becomes stronger the closer we approach the Heart’s core. Negation here by the way, is not a judgement, it isn’t a reference to something wrong or bad. Instead it indicates what is not actual). Again, it’s a very different mode of thinking. Probably, Should, Want, and Able are not of the same category in English, but in Tapissary’s spatial grammar, they share the same distance. Spatiality is not concerned with specific designations such as desire per se, but rather what does it mean to be at the V distance? Basic grammar is similar to English, so things may seem more familiar to us in basic grammar. It is for this reason that I mentioned in another section that Tapissary has two layers of grammar. The two Tapissary grammatical systems approach the world from two different perspectives while remaining compatible. Basic grammar gives us the tools to compose straightforward sentences, while spatial grammar allows us to bare our intuition.

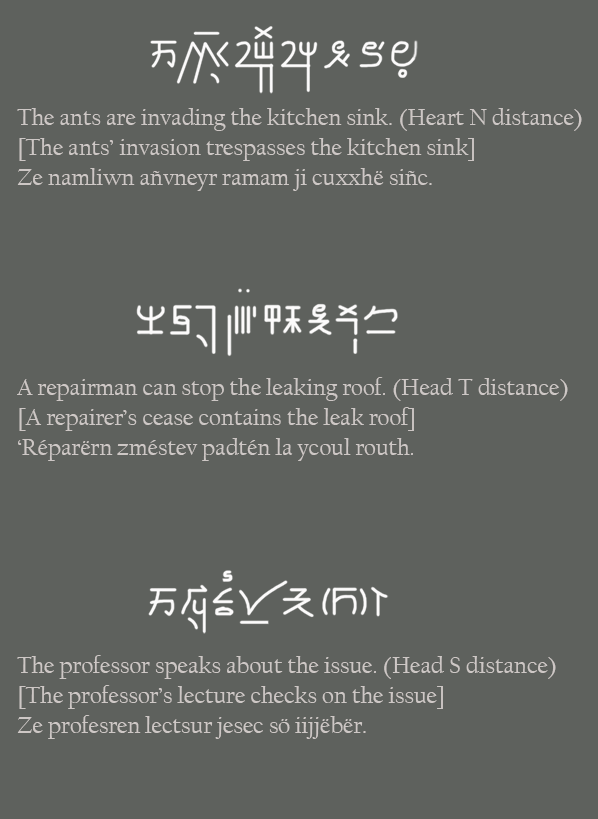

Some more examples of spatial sentences:

In the first sentence which is in the heart state at N distance from its core, there is the emotional response of the ant invasion because it is in the heart state, but the N distance shows us that it is also a real event because it’s so close to the logic of the head state.

In the second sentence, T distance in the head state, this signifies something that is common knowledge. It’s like saying a given: “Repairmen fix roofs”.

In the third sentence, S distance in the head state, the professor is not giving his or her own opinion, but is acquiescing to the University’s wishes.

I will periodically be updating this page. This includes continuing to add new material as well as making corrections and simplifying the wording.