Basic Grammar

The Building Blocks

All languages have grammar, but Tapissary has two layers of it: the basic shown on this page, and Spatial grammar which is built upon the humble structure of basic grammar. So the basic grammar is a central element of the language. While basic grammar is used about 75% of the time, the other 25% is put to good use; Spatial grammar allows the user to express the degree between the actual and the imagined which has become the lifeblood of Tapissary. There will be a separate page devoted to Spatial grammar. (Historic note: Cyclic grammar which has been a part of the language since 1987 was greatly simplified and contributed significantly to the new addition of Spatial grammar in August 2022. Traditional cycles still exist in the literary scope and very formal speech). So before heading over to check out the more advanced facets of Tapissary grammar, this basics page is a good place to start.

The basic grammar is greatly influenced by English (though as you will see later, this is not true of the Spatial system).

DICTIONARY

If you follow the dictionary tab, you’ll see that the vocabulary is written in symbols. There is also a tab on the vocabulary history for those interested in the creation of these symbols. Each symbol, which is called a çelloglyph, also has a pronunciation.

TAPISSARY CAN ALSO BE WRITTEN WITH THE LATIN ALPHABET

I will be transcribing the pronunciation of sentences into the Romanized version of Tapissary along with the çelloglyphs. Please note that the Romanized version is easy enough to read, but not meant to be a strict phonetic alphabet. It has its own spelling personality much as, for instance, French, Spanish, and German do. Please head over to the SPEECH tab for reference on pronunciation and spelling.

LET’S BEGIN…

Here are some phrases. You will notice that verbs do not take conjugation. For example, you say: I like, you like, he like, she like, etc. In the same way, I am, you are, it is, become simplified to; I be, you be, it be.

There is also no change in the direct or indirect pronouns as we have in English. I and me are both simply I. She and her are both she. We and us are both we.

The article “THE”

Now we come to one of the most frequently used words in the language: ‘the’. We have six choices here. One of the roles of this article is to define the physical attributes of the word it describes. In other words, the article ‘the’ is determined by the physical nature of the word it precedes. For instance, when you say, ‘the water’, you use the liquid form of ‘the’. If you say, ‘the wooden board’, you use the hard solids form of ‘the’. If you say, ‘the rock’, you still use the hard solids form of ‘the’. But these forms of ‘the’ are flexible. You are free to exchange them when it’s appropriate. For example, if you say, ‘the rock’, but use the liquid form of ‘the’, this will indicate a molten form of rock, which will be understood as lava. Likewise, an alternative way to say ice is to use the hard solids form of ‘the’ with the word water, because solid water is ice. Be practical, be playful.

Which form to choose?

I use the soft solids to define animals because we have elastic skin. How about rooms and buildings? Their walls are hard solids, but if you say you are going to the grocery store, are the walls the purpose of your visit? But you can alternatively use the soft solids form which indicates the foods you are shopping for. Generalization is the key. Certainly, some items you shop for will be hard solids, but what is the overall picture? It would also be descriptive to use the gas article, because when you are inside of a room, it is an air space. By extension, this is true for reading a computer screen as the brain may be tricked into considering the virtual space an air space. You can always use the compound form because it describes a mix. I try to use the compound only when necessary because the other forms are more descriptive. Where do you suppose someone is going when they say they are off to the (liquids) store? If it’s raining, you can say, the (liquid) traffic was heavy.

The choice is always yours and individual, however some degree of practicality helps ease in communication. Wild application of the article will be more effective if it’s used only on occasion to surprise the listener.

NOTE: ‘The’ is the only article that internally undergoes these changes. But if you want to apply any of the six qualities onto the other articles, place ‘the’ before other articles to give them the same flexibility. Examples: A drink > The (liquid) a drink. We have seven dogs > We have the (soft solids) seven dogs. I know that woman > I know the (soft solids) that woman. Do you understand the my examples above?

EXERCIZE

If you want to try this out, I have a few phrases below that use the vocabulary you’ve already seen above.

1. You are the driver? *

2. I remember the shop.

3. She knows the clerk.

4. The bird likes her.

5. The shop clerk likes the bird?

6. You like the bus.

* NOTE: In Tapissary, questions simply have a question mark after them. You do not reverse the subject and verb for a question the way we do in English. “Are you ready?” is stated: “You are ready?”

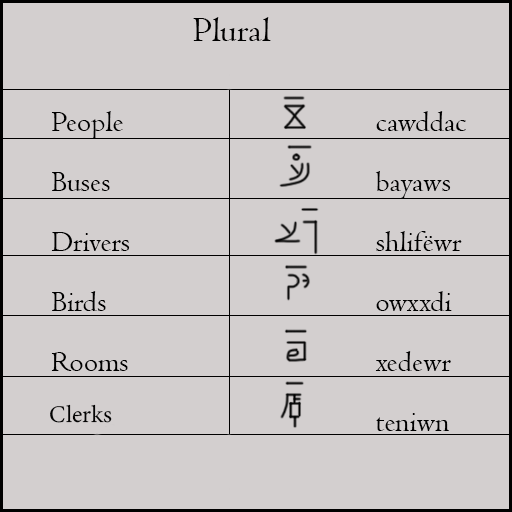

THE PLURAL

GLYPHS

In glyphs, it is shown as a horizontal bar floating above the word. It’s as easy as that, there are no variations.

Plural in the SPOKEN LANGUAGE

In the spoken language, the plural always falls on the last accented vowel of the word. This is easy to tell in the Romanized version. As in French, the tonic accent comes at the end of the word in Tapissary. There is one exception: the vowel preceding a doubled consonant is accented. I’ll write some examples, and capitalize the vowels that receive the tonic accent:

Remember tonamOs

Bus bayAs

Like amrAz

Rain ëshA

Driver shlifËr

The above examples are typical of the tonic accent coming at the end of the word. But in the case of doubled consonants, let’s see how the pronunciation changes:

Bird Oxxdi

Person cAddac

No clerk tEnni *

Rule: follow the tonic accented vowel with the letter W, which always has the value of a full W, as in the word ‘west’.

Buses bayaws

Rains ëshaw

Birds owxxdi

People cawddac

Remembrances tonamows

Likes amrawz

Clerks teniwn

No clerks tewnni

Drivers shlifëwr

* Don’t worry about the negative yet. We’ll see those formations further down.

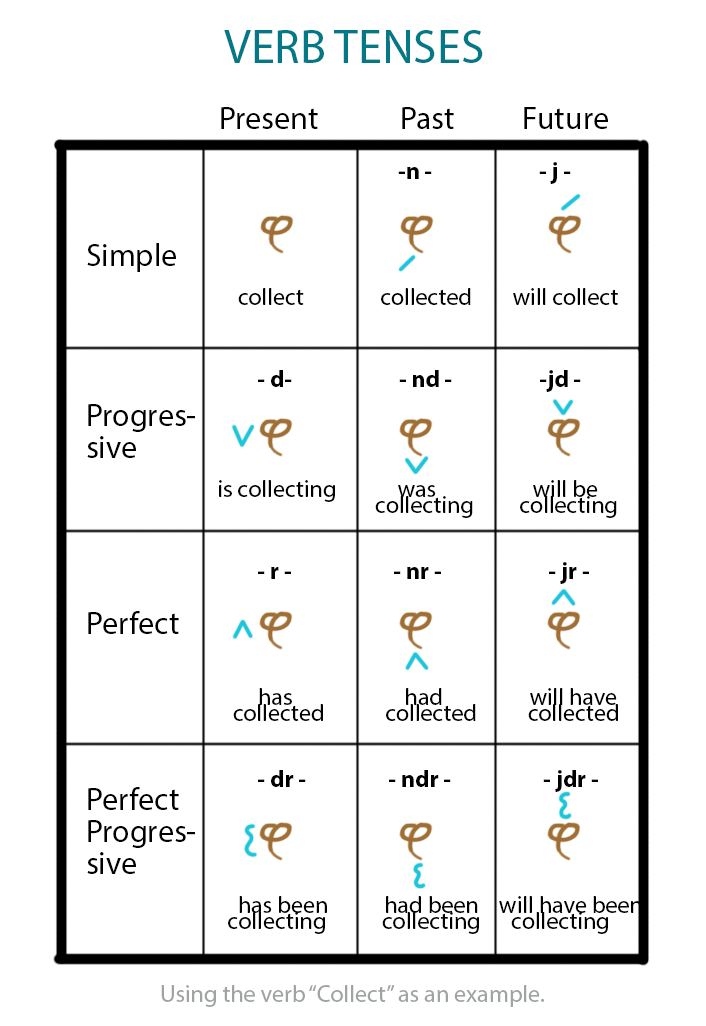

The chart above uses the verb ‘Collect’ as an example. The pronunciation of this word is ksemacr. (Note: please make sure to check the Speech tab for pronunciation. The k in Tapissary is pronounced like the J in July).

I collect …………..Yë ksemacr.

He collects ………….Hlë ksemacr.

The clerk collects……… Ze tenin ksemacr.

The clerks collect ………….Ze teniwn ksemacr.

Notice that the verb form is the same no matter the conjugation. This is true for the present tense as well as all the other tenses.

Above, we saw how the plural marker ‘W’ is placed after the accented vowel of a word. The same applies to verb tenses, with one extra twist. The verb tense snuggles right inside the accented vowel of the word. How is this done? The accented vowel in the verb ksemacr is ‘a’. We need to place the verb tense inside of the letter ‘a’. Let’s take the simple past tense, which is ‘n’, as an example. The ‘a’ is doubled to produce ‘aa’ and accepts the ‘n’ between them, like a sandwich. Ksemacr becomes ksemaacr in which we can now slip in the ‘n’ (past tense), which gives: ksemanacr, which means collected.

All the rest of the verb tenses use the same formula:

I collected ……..Yë ksemanacr (the n is past tense)

She will collect ………Elë ksemajacr (the j is future tense)

The clerk will have collected ……….Ze tenin ksemajracr (the jr is the future perfect)

No clerks were collecting ………Ze tewnni ksemandacr (the nd is the past progressive)

In English, we have lots of suffixes and prefixes, but when a change rests right inside the root of the word, it’s called an infix. As you see above, the plural is an infix, and so are the verb tenses. Next we will see how the treatment of the prepositions is the same as the verb tenses… a kind of sandwich.

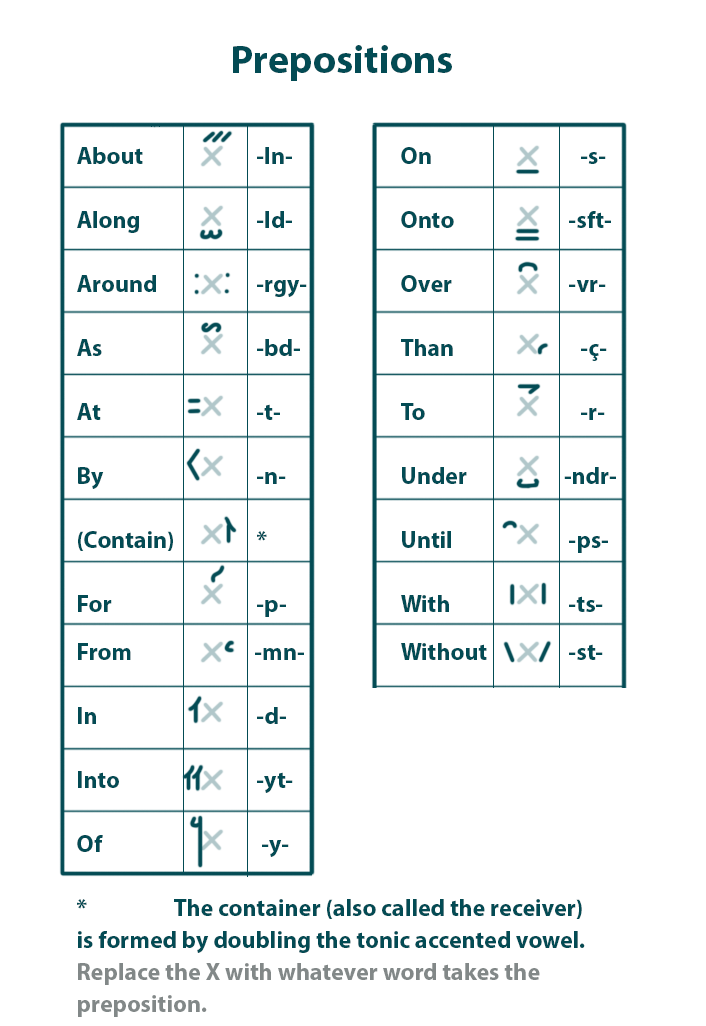

Apology

I always feel guilty when a given section is complex. But there’s no getting around it, prepositions are more involved than other elements of the basic grammar. On the other hand, these prepositional infixes are all treated the same way. Though there is a lot of material to explain, the formula applies across the board for the whole chart. In addition, the system is logical, so while it is quite different, it is neither irregular nor quirky.

History note on tapissary’s prepositions

The peculiar structure of prepositions in Tapissary dates way back to the 1980’s when I devised the system. It has not changed drastically since that time. The logic will be easier to understand when considering that the language was originally pictorial, and in its earliest stages, you could literally draw the subject inside of a glyph for a place, such as a house, to the side of the house, over the house, etc. In one large glyph of a room, I might have a glyph of a person sitting at the glyph for a table eating the glyph for dinner. That isn’t practiced any longer as the glyphs are simple and small, and the writing style is standardized. If you notice the placement of the prepositions which go above, below, or to either side of any word (where the X in the chart stands in for whatever word you wish to attach with a preposition), you will notice that many of them derive indirectly from their pictorial origins. For instance, the X sits on top of the preposition meaning ‘on’, the preposition ‘in’ shows the left wall and roof of a house, indicating that the X is inside of it… and indeed, the receiver is the right side of the house, which completes the enclosure. Actually, you can think of the preposition and its accompanying receiver as quotes around the prepositional phrase(s). Historically, each preposition used to have its own receiver, but long ago, I simplified the system to keep only the one receiver we see today.

FORMULA

As described above in the section about Verb Tenses, the prepositions are also infixes, and are treated in the exact same manner as the verb tenses, in that they are sandwiched between the doubled vowels of the accented syllable.

mechanics

In Tapissary, prepositions come in pairs. Here’s an example: when you sit ON a chair, you are who is sitting upon something, and the chair is that which receives your sitting. If the dog runs INTO the next yard, it is the dog’s running which goes toward something, and the yard which will receive his arrival. With most of the common prepositions, this is how it works in the spoken language: the preposition goes inside the verb, and the receiver goes inside the indirect object. In the written language, the receiver is always the same glyph, but the prepositions have their special positions in relation to the verb. When you read the chart, you will see their proper positions.

The examples above yield:

You sit-on a chair-receiving.

Siñ beses ‘coursii.

(Note above, the article ‘a’ which is “biñ” is simplified to an apostrophe, which when at the front of a word is pronounced as an aspirated P, just the most gentle of puffs with the lips in a relaxed position to pronounce a P, and almost inaudible. The only time I use the word “biñ” is when it precedes a word which begins with a vowel. Tapissary favors both consonant and vowel clusters. It is never wrong to use “biñ”, in fact I had used it to simplify the first exercises on this page, but it sounds formal if it comes before a consonant. Please check the SPEECH tab for pronunciation of double vowels).

The dog run-into the next yard-receiving.

Ze celeps treytex ze naxxritis cortiléé.

As infixes, these forms fit snugly right inside of the word they modify. The verb to ‘sit’ is “bes”. The infix meaning ‘on’ is “s”. We place the “s” right inside of the verb’s accented vowel. So how do we slip the “yt” into the e of the word “bes”? We double the vowel (bes > be-es), and then place the preposition inside of it. Bes + s = Beses.

Examples of inserting the preposition.

‘Run’ is “trex”. We do the same thing here when slipping in the preposition meaning ‘into’ which is “yt”. Trex + yt = Treytex.

Accents always come on the last syllable in Tapissary, unless there is a double consonant. In such a case the previous vowel is accented. In the word “caddac”, it is the 2nd from last a which is accented. CAddac. But in the verb “sixna”, there are no double consonants, so the general rule applies, and the last syllable is accented, sixnA. If we add the “s” to sixna, we get sixnasa. If we add it to caddac, we get casaddac.

INFIX SHORTCUT: You can make the word a little shorter by lopping off the first vowel to the left of the infix, if it is pronounceable. For example, casaddac can drop the first ‘a’ which surrounds the infix ‘s’. This would give 'csaddac’ which is easy enough to pronounce. Sixnasa can be simplified to sixnsa. Even beses can be spoken as bses, but if that is challenging for you to pronounce, using the full form of beses is always an option.

The receiver becomes the indirect object.

That which receives something becomes the indirect object and its accented vowel is doubled. ‘Chair’ is “coursi”, the accented vowel is the i at the end, which gives us “coursii”. In the second sentence with yard, which is “cortilé”, the final vowel is accented, giving “cortiléé”.

What about the prepositions that do not have a specific infix form?

There is no infix for the preposition ‘beneath’ for instance. We will include the word for ‘beneath’ in the phrase and also add an infix to complement it. Choose between either the preposition ‘in’ which complements verbs of state or verbs without obvious motion, or you can choose ‘to’ which complements verbs of motion or direction.

“I crawled beneath the house” is a verb of motion, so we say, “I crawled-to beneath the house-receiving”. However, the word ‘beneath’ isn’t always a motion. “I had a dream beneath a tree” which becomes, “I had a dream-in beneath a tree-receiving”. Note here, that the preposition ‘in’ is not placed on the verb, because there is a direct object between the verb and the indirect object. In these common cases, the preposition goes inside the direct object. Here are some more examples:

The cat drinks milk in the kitchen.

The cat drinks milk-in the kitchen-receiving.

My neighbor expects a delivery at her front door.

My neighbor expects a delivery-at her front door-receiving.

We saw several chairs beyond the road.

We saw several chairs-in beyond the road-receiving.

Changing the order of the phrases

You can place a prepositional phrase at the very beginning of the sentence, and in such a case, the infixes are not used. Generally, introductory prepositional phrases deal with time: “In a year”, “Until the next time”, “At dinner time”, etc.

Masculine and Feminine

As we saw above, the infixes can be dropped when a prepositional phrase initiates a sentence, but there is a case when the infixes can be dropped right inside of the sentence proper. The masculine and feminine forms are present in the third person in English (he and she), but in Tapissary, it can be extended to the first and second persons too (I, you). This is not shown via vocabulary words, but is rather expressed through the use or lack of prepositions. While this is not always the case, women tend to be more expressive in their communications, and men tend to be more direct. In Tapissary, the feminine is expressed by an additional preposition where it otherwise would not be expected. For example, You (feminine) bought the book = You bought-in the book-receiving. Which infix best fits your needs is your choice. In contrast, a sentence with a preposition drops the infix if the subject is masculine. For example, I (masculine) am at the computer = I am at the computer (neither infix nor receiver figure into this phrase). You do not have to use this application if the subject of the sentence is already one sex or the other. You don’t need it when a sentence begins with She or He, or if it is a common name like John or Susan. You would need it in the third person were you unsure of the sex, for instance, “Dr. Trimas prescribed the medication”, if your listener does not know if Dr. Trimas is male or female, you could clarify.

NOTE: Using the feminine and masculine modes is an option, but not required.

TROUBLE SHOOTING: What if you wish to use the feminine in a sentence that already has a prepositional infix in it? Answer: you add yet another where it would not ordinarily belong. Example for Feminine: “I live in Tokyo” already has a preposition. You now need a direct object in addition, and you will force that direct object to become an indirect object, and thereby make it clear that ‘I’ in this sentence is female. Take this for instance: I live in Tokyo > I have my residence in Tokyo. The word ‘residence’ is the direct object. Now we can make that an indirect object yielding: I have-by my residence-in Tokyo-receiving. (The placement of the receiver in this example will be easier understood if you read the next section down about sentences with two or more prepositions). Another way you can approach this is to add an incomplete object which means, you use a preposition but do not add the object after it. I’ll show you how this suggests something without specifying it. “I live in Paris by…” (Yë anxëdë Parnis) What does that mean? It depends on the context of the sentence, so it might mean you live ‘by the river’, ‘by the Arc de Triomphe’, etc. “You bought at…” (Siñ lenten) is a perfectly acceptable phrase in Tapissary. One caution with the incomplete object. While it generally is assumed to be indicating a female subject, this is not always the case if it stands alone. “You bought at” could also be a male subject when dropping the infix (Siñ lenen i) But when it is in combination with another prepositional phrase containing an infix such as “I live in Paris on” (Yë anxëdë Parsis), then we know for sure it is a female subject.

And now for the example for Masculine: If the sentence has no prepositions, add one. “You have an apartment” > “You have an apartment in Paris”. To clearly show that ‘you’ is masculine, we must remove both the prepositional infix and receiver that would have existed in this sentence, thus giving: “You have an apartment in Paris” (Siñ xa biñ apartmañ ydrou Paris), word for word the same as in English. The incomplete object can also be used for the masculine, but the preposition is in its full form, and not an infix: “I have been reading this book for” (Yë ledren du cipbiñ fi) uses no infixes and has no receiver. The masculine phrase can also be further shortened if the context is understood. Say someone wants to know about your trip to Tahiti and asks if you enjoyed swimming there. Your response could be, “I the ocean”, which would convey that you did enjoy swimming in the ocean. In this phrase both the verb and the preposition are dropped. Other examples, “I’ll meet you six (o’clock)”, “Remember to put potatoes the oven”, “Be quiet and sit the chair!”

WHAT HAPPENS WHEN A SENTENCE HAS TWO OR MORE PREPOSITIONS?

As you now know, when you use a preposition, it has its receiver compliment. But in the case of having more than one preposition in a sentence, I’ll show you what happens. Here’s an example of a sentence with multiple prepositions: “He lives IN a little house UNDER a tall tree ON a hill IN a nearby town.” There are 4 prepositions in that sentence which forms a string of prepositional phrases. A string only needs one receiver at the very end of the phrase. It is grouped like this: He lives-in a little house-under a tall tree-on a hill-in a nearby town-receiver. The order you place the prepositions should follow logic. Were you to say, “he lives in a house in a nearby town on a hill”, you might conclude that the town itself is on a hill. If the town is predominantly flat, but has a hill or two, it would be clearer to place ‘hill’ after ‘house’ to show it is the house which is on the hill, and follow ‘hill’ by ‘in a nearby town’.

He lives in a little house under a tall tree on a hill in a nearby town.

PREPOSITIONAL PHRASES SEPARATED BY A CONJUNCTION

When you have two or more prepositional phrases in the same sentence, but they are separated by a conjunction such as ‘but’, ‘and’, ‘if’, etc., each phrase retains its own receiver.

She is under the impression THAT the room is in the French style.

Elë ndri sö iñprees sa ji xeder di ji frañs toouxxet.

He paints in the impressionistic style BUT he teaches about the modern style.

Hlë piñdredet la iñpresic toouxxet go hlë labdaz sö sisxon toouxxet.

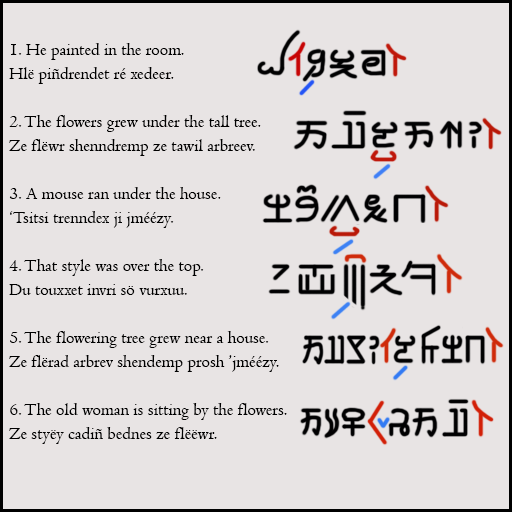

COMBINING THE VERB TENSES WITH THE PREPOSITIONS

Ready for some chemistry? In a sentence such as “He painted in the room”, the verb paint gets both the preposition ‘in’ and the past tense infix at the same time. Both infixes precede the accented vowel. First you place the verb tense, which in this case is ‘n’, and follow it immediately by the preposition, which here is ‘d’. The verb paint is piñdret, so we get painted as piñdrenet, and painted-in as piñdrendet. “He painted in the room” becomes “Hlë piñdrendet ré xedeer”. Now if you look on the verb chart you may notice an overlap; ‘nd’ is also the past progressive which you might think at first means “He was painting the room”. But because room (xeder) is in the receiving form of xedeer, you know by context that there is a preposition acting on it, and therefore understand that piñdrendet does not mean “was painting”, but it means “painted in”. The formula is: first comes the verb tense followed by the preposition.

ABOVE: Examples of prepositional phrases. The blue markings are the verb tenses. The red markings are the prepositions and receivers. Notice that in each phrase, the end has the same marker which is the receiver. The receiver is always written the same, no matter with which preposition it is paired.

For the spoken phrases above, do you notice in #2 and #3 that the past tense next to the preposition cause a double consonant? In #2 we see "shenndremp". The first ‘n’ is the past tense, the ‘ndr’ is the preposition meaning under. Because they cause a double consonant, the rule still applies here that the accented vowel is now the one preceding the doubled consonants. It would sound like this: shEndremp, and not shendrEmp. The same for trenndex in #3, which sounds like: trEndex.

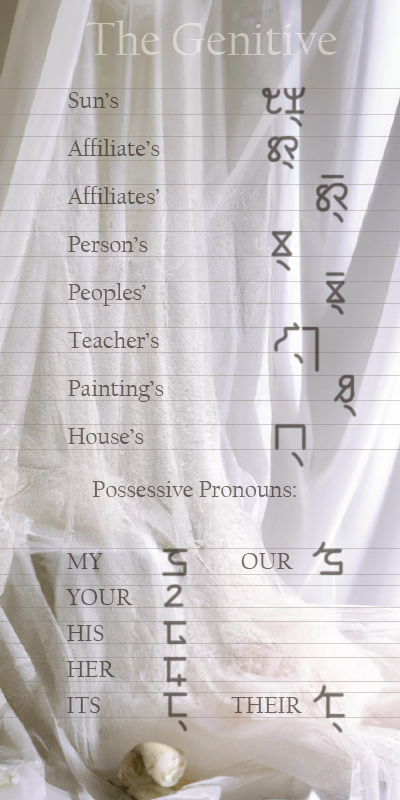

The Genitive (Possession)

In English, you show possession by placing an ‘s after the noun. In Tapissary you add an n. If the word ends in a consonant which is awkward with the n, then repeat the previous vowel and place that before the n. It’s as simple as that, the genitive is a suffix, not an infix.

Sun’s Zbarci + n = Zbarcin

Affiliate’s Afili + n = Affilin

Affiliates’ Afiliw + n = Affiliwn

Person’s Caddac + n = Caddacan

Peoples’ Cawddac + n = Cawddacan

Teacher’s Lazër + n = Lazërn

Painting’s Piñdret + n + Piñdreten

House’s Jmézy + n = Jmézyén

POSSESSIVE PRONOUNS:

MY Jda OUR Jdë

YOUR Jdé

HIS Cré

HER Cañjo

ITS Jdi THEIR Jdir

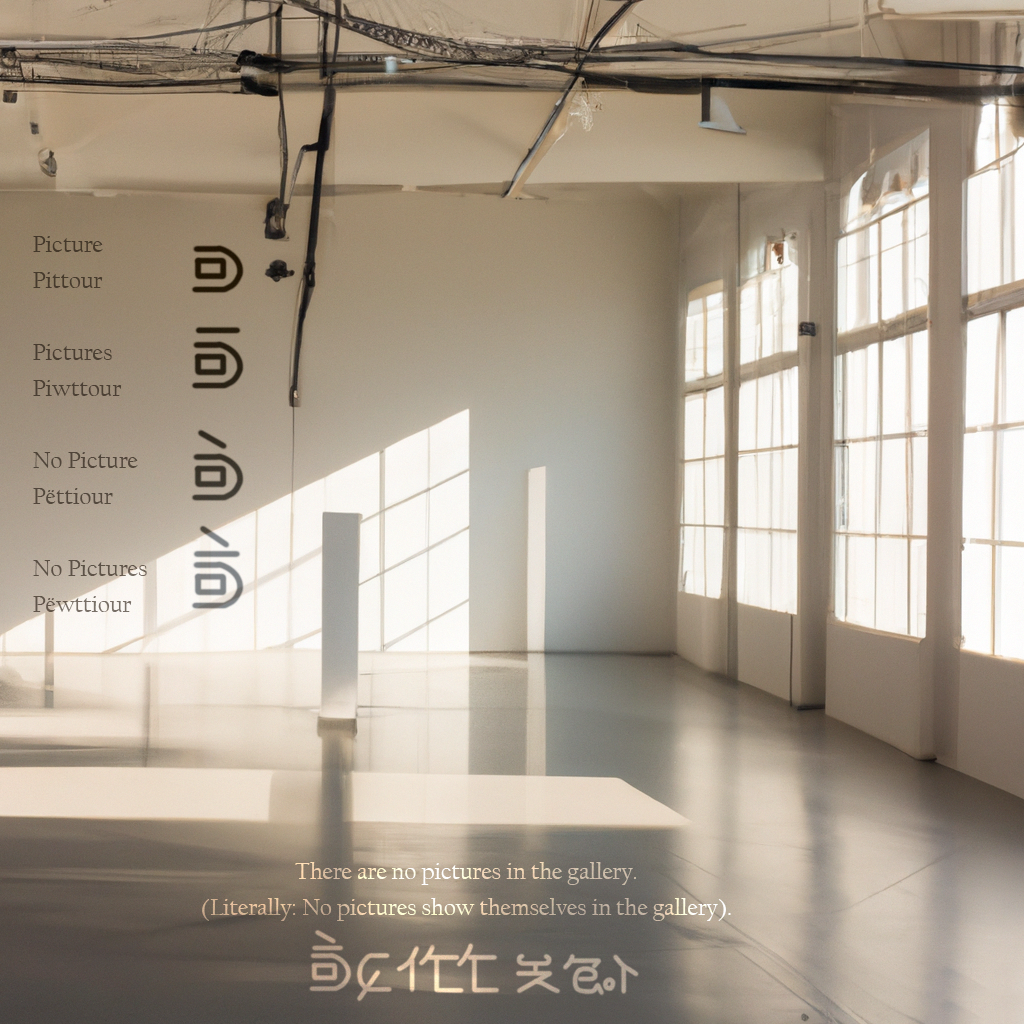

The Negative

There are no pictures in the gallery > Pëwttiour miseb larladar ré galérii.

Written form:

The negative is written by a backward slash over the glyph.

Spoken form:

The negation in basic grammar is formed by way of an infix. (You will see later that the negative is handled differently in spatial grammar).

A negative part of speech in Tapissary has its accented syllable inverted. Since the negative negates whatever word it describes, be it a verb, noun, or adjective, you confound the root of the word by reversing the syllable as a symbolic gesture of extreme contrast. Take the accented vowel (or diphthong) of the word and exchange its place with the consonant or consonant cluster that follow it. If the word ends in a vowel, then the preceding consonant (or consonant cluster) is that which is switched.

Negated words ending with an accented vowel:

Have – xa

Not have – ax

Enjoy – shërab

Not enjoy - shërba

Book - cipbiñ

No book – ci’iñpb

Notice - ilañ

Not notice - iañl

Happy - ënë

Unhappy – ë’ën

NOTE: If the same vowel repeats itself as in the cases above of ci’iñbp and ë’ën, an apostrophe helps clarify that these vowels each have their full pronunciation, and are not read as if they were the double vowels of the indirect object, i.e. the receiver.

Negated words ending with a consonant:

When two or more consonants come together, sometimes they are easy to pronounce, while other times they are awkward. In the case of a difficult cluster, add the ë between the two neighbors to relax the pronunciation. For instance, pie is purtarj. If you want to say no pie, then you break the word apart like so, purt+arj > purt+rja > purtjra. While this might not present a problem of pronunciation for some people, it is a rather heavy consonantal cluster. By placing the ë between the two clusters seen in this example, it is easier to pronounce and hear. Purtrja would yield purtërja.

Other infixes do not conflict with the negative. On this word for pie, for instance, you can add the plural, and a preposition. The same rules described about other infixes apply without any modification to their position. It is entirely regular.

Examples:

A) on accented vowels on the last syllable.

Pie – purtarj

No pie – purtërja

No pies – purtërjaw

No pies at – purtërjataw

… … … … … …

B) On accented vowels that are not the last syllable.

We must preserve the accented syllable before the double consonant. Therefore, the accented syllable is reversed as usual, but the ë is placed before the doubled consonant. Pittour > Pttiour (do you see here where no vowel precedes the double tt? This is why the ë is inserted). Pttiour > Pëttiour (now the correct syllable is accented).

Picture - pittour

No picture - pëttiour

No pictures - pëwttiour

No pictures in - pëdëwttiour

.

Squeeze – caddig

Not squeeze – cëddaig

Did not squeeze - cënëddaig

Will not be squeezing - cëjdëddaig

The Passive

Formation of the Passive

The passive verb becomes a noun, and the verb ‘get’ precedes it. For instance, in the sentence “The train was heard for miles around”, we turn ‘was heard’ into ‘a hearing’, or any noun you feel best replaces the verb ‘to hear’. For this demonstration, I’ll use the noun ‘ear’. This gives: “The train got an ear for miles around”. You can expand however you like. Here’s another example “The train got an audial reaction for miles around”.

Including the agent.

If you know by whom something is done, generally the preposition ‘of’ is used.

“The train was heard by the neighbors”. The neighbors are the ones who are hearing the train, so the sentence becomes: “The train got the ears of the neighbors”. Another example, “I was promised an early delivery by the company”. This becomes, “I got a promise for an early delivery of the company”.

The train got an ear for miles around.

Ré wtriñ xanasyl biñ örpey miiwl saviv.

The reason I used the gas article (ré) for the train is to emphasize its distance. The further away something is from us, the more it mixes with the atmosphere. You can use any article you feel best fits. Ze would have indicated your focus on the passengers, while Ji would have described the physical structure of the train.

The passive as an adjective.

When an adjective is passive, -nou is added to the adjective.

Unite - uni

United States - Uninou Cuicuiw

Surprise - Éthov

Surprised reaction - Éthovnou moseç.

The Imperative

(The command form)

Now for some easy stuff. There are no infixes, prefixes, suffixes, or conjugational concerns for this application. Quite simply, add the word ‘That’ (Sa), or ‘What’ (Ca) in front of the phrase. Using ‘what’ is softer than using ‘that’. Using ‘that’ is derived from English and some other European languages that place ‘that’ before the subject and verb to produce a command usually for the third person. In Tapissary, the imperative can apply to first person through third person. The word ‘let’ is also used the same way, being replaced by ‘that’ or ‘what’. In English we drop ‘you’ in the command form, but in Tapissary, you just leave the verb structure alone, but precede it with ‘that’ or ‘what’.

Sa siñ pops up so frequently, that it can be abbreviated to s’. Here is an example: That you call = Sa siñ xazmin, or simply: s’xazmin. Ca siñ can also be abbreviated to c’ giving: C’xazmin.

Fetch the disks!

That you fetch the disks!

Sa siñ faleps ze diwsscous!

(Or you can shorten it to: S’faleps ze diwsscous!)

Let’s wash the dishes.

That we wash the dishes.

Sa xir wésh ji tasbawx.

Please come back later.

What you back come later.

Ca siñ ahoi yelmëz axaron.

Shorter version: C’ahoi yelmëz axaron.

Tell me a story.

What you tell a story to me.

Ca siñ leyleh ‘yistwarar yëë.

Shorter version: C’leyleh ‘yistwarar yëë.

Fill out the forms in triplicate.

That you out fill the forms in 3 copy. (Note: copy does not need the plural since a number precedes it).

Sa siñ üle rañpli ze cöldiwb ti coptëër.

Shorter version: S’ulë rañpli ze cöldiwb ti coptëër.

Numbers

Counting (The numbers)

This is a system I made in my adolescence, and it persists today with very little change. Several years ago, I did experiment with an alteration only temporarily, and in the end, I decided to keep the original which stands firm today.

The numbers used to have their own glyphs, but for a couple decades now, Tapissary, like most of the world uses Arabic numerals. The only difference is, you can place a comma under the first digit of any single or group of numbers to distinguish it from other glyphs. For instance, the number two ‘2’ is the same as the glyph meaning ‘your’, and the number three looks like the glyph for ‘with’. But using the comma under a number is not a requirement, it just makes it easier to read.

When numbers or other qualifiers of counting such as ‘many’, ‘numerous’, ‘tons of’, ‘barely any’, come before a noun, it is not necessary to add a plural marker. “The duck ate a good number of crumb”, “There were only 3 piece of mail today”.

In the one’s column, we stick the ‘i’ onto the root, except for zero.

0 zéro

1 ci

2 ri

3 ti

4 fi

5 ni

6 si

7 vi

8 mi

9 xi

In the ten’s column, we replace the ‘i’ with ‘a’.

10 ca

40 fa

55 nan, or nani

76 vas, or vasi

94 xaf, or xafi

The ‘i’ is the only vowel that can be dropped. It cannot be dropped if it is a single digit, however. If you say I have one book, it is: Yë xa ci cipbiñ. You would not say: Yë xa c cipbiñ. But in any other combination with two digits or more, the ‘i’ can be dropped.

In the hundred’s column, we use ‘o’.

100 co

450 fona

456 fonas, or fonasi

803 mot

132 cotar

One thousand and above, we add words.

1,000 ci thousañ

3,333 ti thousañ totat

560,099 nosa thousañ xax

801,004 moc thousañ fi

Million is milyoñ, and billion is bilyoñ.

10,007,321,005 ca bilyoñ vi milyoñ torac thousañ ni

Adding the plural.

Like any other word, the numbers can receive the plural and affixes.

Thousands arrived for the festival.

Thousañ in the plural is regular, giving Thousañw.

We saw thousands of birds.

In this sentence, ‘thousands of’ is both in the plural and has the preposition of ‘y’.

Thousañyañw. Also remember that the first vowel before an infix can be dropped if it’s easy enough to pronounce, therefore, it is shorter to say ‘thousands of’ as Thousyañw.

Numbers can also be placed in the negative.

1 = Ci

Not 1 = Ic

15 = Can

Not 15 = Cëna

2,075 = Ri thousañ van

Not 2,075 = Ri thousañ vëna

Millions = Milyoñw

Not millions = Mioñwly (Note: this is a sweet sounding cluster, but if it’s too hard to pronounce, you can add an ë after the w, giving: mioñwëly. If you do this, please keep in mind that the ë is only a trainer, and therefore does not receive the tonic accent. The accent remains on oñ.

stories

The dark green sign in the left of the photo reads: Bus Stop.

The sign with the dog wearing a hat says: Sandwich Thief! If you have any information...

The Bus Stop

Ré Bayas Bdalla

Jérémi attañd ré bayas bdaalla.

Jeremy waits at the bus stop.

(Notice that atañd + the preposition ‘t’ = attañd. See how the tonic accent shifts due to the double consonant?)

Fi ci avcath, hlë atañdrañd, na hlë atjañd dé ji bayas ba.

He has been waiting for one hour, and he will wait until the bus arrives.

(Literally: For one hour, he has been waiting, and he will wait until the bus arrives).

‘Cyor deen miseb iltil ré bayas bdaalla. Cawddac i carçouçou crëytuwr.

There is a lot to see at the bus stop. People are funny creatures.

(Literally: A lot of see shows itself at the bus stop. People are funny creatures).

Jérémi déjen jdir tasaruf.

Jeremy observes their behavior.

Go hlë i çiñth. Ydrou fassër, hlë i ysis çiñth hlë cëirt al xatoul shraci.

But he is hungry. In fact, he is so hungry he could eat cat food.

Jérémi rëmu cré svans na nakous ze addañ prosh hlëë dojon ‘trététh hlëë.

Jeremy wags his tail and hopes the man near him will give him a treat.

(Literally: Jeremy wags his tail and hopes the man-in near him will give a treat-to him).

‘Thöyöth miseb ildil cré zmeen.

There is a sandwich in his hand.

(Literally: A sandwich shows itself-in his hand).

Go ze adañ iañl hlë. Ysis, Jérémi belt.

But the man does not notice him. So, Jeremy barks.

(Note: the verb ‘notice’ is ilañ. The negative is iañl.)

Stil, ze jovañ adañ mabist drwapliñ mtafdam, na pyé vnimtañ ré beelt.

Still, the young man looks straight ahead, and does not pay attention to the barking.

(Note: To pay is péy. Not to pay is pyé.)

Go sö biñ olo miseb ilil sa ytou celewps lahha: Jérémi satsir ze adañn xoupaash.

But there is a trick that all dogs know: Jeremy pees on the man’s shoe.

(Literally: But the (abstract form) a trick shows itself that all dogs know).

Ze jovañ adañ tosbir, na padinna lash ze thöyöth.

The young man jumps, and thus drops the sandwich.

Jérémi caw tretsex ze trofdé cré beesh.

Jeremy runs off with the trophy in his mouth.

(Literally: Jeremy off runs-with the trophy-in his mouth).

Hlë ytrov otrui bayas bdalla na atañdañd shañ pourjyañz doollçé.

He finds another bus stop and waits there in pursuit of dessert.

Ze Péppër Pipër.

The Pepper Piper: The strangest things happen in lands where Tapissary is spoken!

Sa rawt xasyl ‘pyañ!

Rats be gone!

(Literally: That rats get a going! Notice that I’ve used both the command form and the passive together here).

Ze mesapyol Tileeppery xanasyl ‘namletses raawt.

The city of Tileppery was infested with rats.

(Literally: the city of Tilyeppery got an infesting with rats).

S’xazmin ze pipër! Ze cwanos comnañd.

Call the piper! Ordered the queen.

Jebbër ze pipër banta ré rwayal saxneet, hlë misafner ‘maynific pitsip hlëë.

When the piper arrived at the royal court, he carried with him a magnificent pipe,

(Literally: … he carried a magnificent pipe with him),

Na nowibbya hlë, ‘tsajir liyiyyin shxandenad raawt ni.

and behind him was a little line of admiring rats.

(Literally: and behind him, a little line of admiring rats were).

“Sodiyyid” ze cwanos dnih, “Siñ yvavan adtxi ze rawt”.

“Indeed” said the queen, “you herd the rats well”.

“Go smboñ ysis fyiñ miseb larlar?

“But why are there so few?”

(Literally: but why so few show themselves?)

“Jda cwanos” cré rada yelmnëz, “Nö majyen, jda péppër ulë trenex, ysis y’turoz dahha lañbëtre boyavo ré pip. Y’hethiyon péppër fi hanaz jda haytahha ji iñstrumaañ.

“My queen” came his response, “My pepper ran out this morning, so I can no longer play the pipe. I need pepper to sneeze my breath into the instrument”.

(Literally: “My queen” his response came, “Now morning, my pepper out ran, so I can more not-long play the pipe. I need pepper for sneeze my breath-into the instrument).

Mout ‘volcérn ydimaj, ze cwanos vuipsañnañs.

What an awful image thought the queen.

(Literally: True an awful image, the queen thought).

Cañjo pañl ox xanasyl bethwen, go elë récupner na dnih:

Her pale complexion was noted, but she recovered and said:

(Literally: Her pale complexion got note, but she recovered and said):

“Siñ xaja ytou ze péppër jdé hana dézir”.

“You shall have all the pepper your nose desires”.

“Na fya siñ tsilim ydrou ulë xada ze ryawt taanna, siñ xaja ‘finos faribdif öduul”.

“And if you succeed in leading the rats out of town, you will have a fine farm as reward”.

(Literally: And if you succeed in out leading the rats-of town, you will have a fine farm as reward).

Ze péppër pipër hanndaz reconésaañ, sa prodnuy ‘fyiñ bethwedewn ré scyalla Bé iyyi minëër.

The pepper piper sneezed in gratitude, which produced a few notes in the scale of B flat minor.

Nö, ydrou saw dëw, péppër ni tsnou fadafadda, na rawt ni tsnou romén.

Now, in those days, pepper was very expensive, and rats were very common.

Wdo zamañ ze rawt xanasyl biñ ayër xada; lar rëknour ‘tash axaron.

Each time the rats were lead away; they returned a year later.

(Literally: Each time the rats got an away leading; they returned a year later).

Wdo tash, ze cwanos réxennoury cañjo plej.

The queen renewed her pledge each year.

Ysis, ze péppër pipër zenéndéhhou tsnou kamañ ci caaccouri.

So, the pepper piper became very wealthy within a decade.

Cré ci farif shenremp merii, na oubiñ ‘nöbl adañ, cré hanawz benest hlëmnë ytou aawnndëcë.

His one farm grew to many, and as a nobleman his sneezes distinguished him from all others.

Ze cawddac dnih hlë ni biñ efferiv pipër, na lar mezcnët hlë ze myayr Tileeppery.

The people said he was an effective piper, and they made him the mayor of Tileppery.

Hlë xanasyl diyissonkiy dëwdduiken ha rëtaw.

He was disrespected by neither citizens nor rats.

(Literally: He got disrespect-of no-citizens or no-rats). Here we see the negative forms of nouns. Citizens is Duwddiken. No citizens is Dëwdduiken. Rats is Rawt. No rats is Rëtaw.

Azzi na thary rat anxënë ënë pañdoté eppita.

Everyone and every rat lived happily ever after.

Poseidonon Relm

Poseidon’s Realm

Xir vuipsañs hlë i ‘miith.

We think he is a myth.

(Note: the word miith is a rare case where a double vowel is part of the root word. It is pronounced as an elongated i. In other words, each ‘i’ in the word gets its full, normal pronunciation).

Ydrou cadim dëw, lar denen hlë shamnar la maar.

In ancient days, they saw him rise from the sea.

Ydrou ze sisxon vorlda, hlë xarasyl kahma ha bishvëli.

In the modern world, he has neither been encountered nor believed.

(Literally: … he has gotten no-encounter or no-belief.)

Go hlë indri htar, la wééwf.

But he is here, under the waves.

‘Yistwiiñ i ytou poutrë, go Poseidon navvi cré zamañ masçrov tsajir kanpyañ dofiwn ytrov jdir matther.

A god is all powerful, but Poseidon spends his time helping little stray dolphins find their mother.

(Note: TH is pronounced the same as in our word ‘mother’. The double T shows it is a double TH, and therefore the tonic accent precedes the double consonant sounding like this: MATH-er. We see the same type of thing in the word for father ‘Fetther’ sounding much like the English word Feather. Also, to note, in the word Yistwiiñ, this is not a double iñ. There are two separate vowels next to each other in the root of this word, each getting their full pronunciation i + iñ).

Hlë masçrov ze étuil pisis shë praer ‘jamsaballa.

He helps the starfish who has lost a leg.

Hlë dovest jrurur wéwf ahoi tir ze plajnou baliñytiñ la oshiaanno.

He brings huge waves to pull the beached whale back into the ocean.

Go sö mitralyic Poseidoon shëirt ri misxada.

But the gentleness of Poseidon should not be misleading.

Fya hlë xasyl crwa, ze yistwiiñ turoz siñc ‘kzaner, hatsife ‘continent, ha mastheth tö añtyer ytërth ‘lajör vorldaa.

If he is crossed, the god can sink an island, flood a continent, or turn the entire Earth into a water world.

Hlë i mitralic na discré, oubiñ lañbetr oubiñ xir i tsë.

He is gentle and discreet, as long as we are too.